When you switch to a generic drug, you expect the same effect as the brand-name version. But what if your body reacts differently-not because of the pill, but because of your genes? This isn’t theory. It’s happening right now, in kitchens across the UK, in hospital pharmacies, and in GP offices where patients are told, "It’s the same medicine," only to end up with side effects or no relief at all.

Why Your Family Tree Matters More Than You Think

Your parents’ reactions to medications might be written into your DNA. If your mother had a bad reaction to statins, or your father needed a much lower dose of warfarin after a stroke, that’s not just coincidence. It’s pharmacogenetics-the study of how your genes affect how you process drugs.

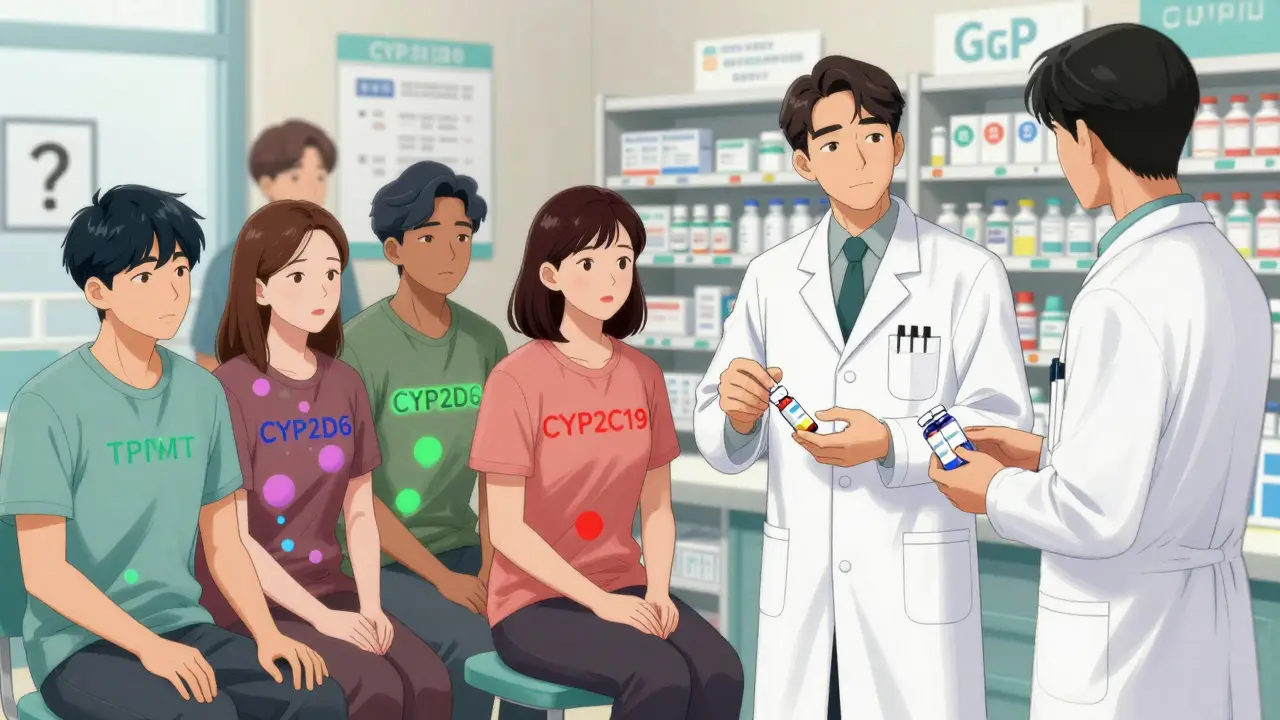

Genes like CYP2D6, CYP2C9, and TPMT control how fast your liver breaks down medicines. Some people have versions of these genes that make them ultra-rapid metabolizers. They clear drugs too quickly, so the medication doesn’t work. Others are slow metabolizers. Their bodies hold onto the drug too long, leading to toxicity. These variations are inherited. If your sibling had a dangerous reaction to a common antidepressant, you could be at risk too.

Studies show genetic differences explain 20% to 95% of why people respond differently to the same drug. That’s not a small range-it’s the difference between a medicine saving your life and putting you in the hospital.

What Happens When You Switch to Generics

Generics are required by law to contain the same active ingredient as brand-name drugs. But they’re not identical. Fillers, coatings, and manufacturing processes vary. For most people, this doesn’t matter. But for those with genetic sensitivities, even tiny differences in how a drug is absorbed can tip the balance.

Take clopidogrel, a blood thinner. It’s a prodrug-meaning your body must convert it into its active form using the CYP2C19 enzyme. About 15-20% of people of Asian descent have a genetic variant that makes this conversion nearly impossible. If they switch from a brand-name version to a generic, they might not notice any difference in price-but they could be at high risk for a heart attack or stroke because the drug isn’t working.

Another example: paroxetine, an SSRI antidepressant. If you’re a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer, your body can’t break it down properly. Even a standard generic dose can build up to toxic levels, causing serotonin syndrome-symptoms like confusion, rapid heartbeat, and muscle rigidity. One patient in Birmingham told me, "I took the same generic sertraline my doctor prescribed for years. Then they switched me to a different brand. I felt like I was having a nervous breakdown. Turns out, the new version had a different filler that changed how fast it released into my system. My gene test later confirmed I’m a slow metabolizer. They never asked about my family history."

Genes That Change Everything

Some gene-drug pairs have been studied so thoroughly they’re now part of clinical guidelines. Here are the big ones:

- CYP2D6: Affects 25% of all prescription drugs-including codeine, tamoxifen, antidepressants, and beta-blockers. Over 80 variants exist. Poor metabolizers get no pain relief from codeine; ultra-rapid metabolizers can overdose on it.

- CYP2C9 and VKORC1: Control warfarin dosing. People with certain variants need up to 50% less. Getting this wrong leads to dangerous bleeding or clots.

- TPMT: If you’re being treated for leukemia or autoimmune disease with thiopurines (like azathioprine), this gene determines if you’ll develop life-threatening low white blood cell counts. Testing before starting cuts severe side effects by 90%.

- DPYD: For patients on 5-fluorouracil (a chemo drug), a single variant can cause fatal toxicity. Testing is now standard in UK oncology units.

- HLA-B*15:02: Carriers of this gene (common in Southeast Asians) can develop Stevens-Johnson syndrome from carbamazepine, a seizure and mood stabilizer. Screening is mandatory in some countries.

These aren’t rare conditions. One in five people carry at least one high-risk variant. And if your family has a history of unexplained drug reactions, your odds go up.

Population Differences Are Real-and Overlooked

Genetic risk isn’t the same for everyone. A variant that’s rare in Northern Europeans can be common in West Africans or South Asians. For example:

- African ancestry patients often need higher warfarin doses due to variants in CYP2C9 and VKORC1.

- Up to 20% of East Asians are poor metabolizers of proton pump inhibitors (like omeprazole), meaning they get less acid relief from standard doses.

- The rs622342 variant linked to metformin intolerance is far more common in African and Tunisian populations than in Europeans.

But here’s the problem: most dosing guidelines are still based on data from white European populations. If your family came from Jamaica, Pakistan, or Bangladesh, and you’re told to take the "standard" dose, you might be getting it wrong.

What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t need to wait for your GP to order a test. Start with your family history.

- Ask relatives: "Did anyone in the family have a bad reaction to a medicine?" That includes rashes, nausea, dizziness, or no effect at all.

- Write it down. Note the drug, the reaction, and the person’s relation to you.

- Bring it to your next appointment. Say: "I have a family history of bad reactions to certain drugs. Could we check if any of my meds are affected by my genes?"

Tests are available. In the UK, the NHS offers targeted testing for high-risk drugs like thiopurines and 5-FU. Private panels (like Color Genomics or OneOme) test 15-20 genes for around £250. Some private insurers cover it if your doctor requests it.

And here’s the kicker: if you’ve had a bad reaction before, you’re already a candidate for testing. You don’t need to wait until you’re hospitalized.

Why Doctors Don’t Always Ask

It’s not that they don’t care. It’s that most weren’t trained for this.

A 2023 survey found that 79% of UK GPs say they don’t have time to interpret genetic results. Only 32% feel confident using pharmacogenomic guidelines. Electronic health records rarely flag genetic risks. Even when a test is done, the result often sits unread in a file.

But change is coming. The NHS is piloting preemptive testing in several regions. Mayo Clinic’s program found that 42% of patients had high-risk gene-drug matches-and 67% of those led to safer medication changes. That’s not a small win. That’s life-saving.

Pharmacogenomics isn’t science fiction. It’s already in use in cancer wards, psychiatric clinics, and cardiology units. The only thing missing is awareness.

The Future Is Personal

By 2025, 92% of UK academic hospitals plan to expand pharmacogenomic testing. The All of Us Research Program in the US is already returning genetic results to over a million people. The UK’s own Genomics England is building a similar national database.

Imagine this: you walk into your GP, your prescription prints out, and the system automatically checks your DNA profile. It says: "This generic metformin may cause nausea. Consider a different formulation. Your CYP2C19 status suggests you’ll need a higher dose of clopidogrel."

That’s not a dream. It’s the next five years.

For now, you have power. Know your family history. Ask questions. Don’t assume a generic is always safe. If your body didn’t respond well before, it might not now. And if your doctor dismisses your concerns, ask for a referral to a clinical pharmacologist. Your genes aren’t just part of your story-they’re part of your treatment plan.

Can my family history really affect how I respond to generic drugs?

Yes. Genetic variations passed down from parents directly affect how your body breaks down medications. If relatives had unexpected side effects or no response to drugs like warfarin, antidepressants, or statins, you may share the same gene variants. These can make you a slow or fast metabolizer, changing how effective or safe a generic drug is for you.

Which genes are most important for drug response?

The top genes are CYP2D6 (affects 25% of all drugs), CYP2C9 and VKORC1 (warfarin), TPMT (chemotherapy drugs like azathioprine), DPYD (5-fluorouracil), and CYP2C19 (clopidogrel, proton pump inhibitors). These have well-established clinical guidelines and testing is routinely recommended before starting treatment.

Are generic drugs less safe than brand-name ones?

Not inherently. Generics contain the same active ingredient and are approved by regulators. But for people with genetic sensitivities, differences in inactive ingredients or release rates can trigger reactions. If you’ve had a bad reaction to one generic, switching to another might not help. Genetic testing can tell you if your body is the issue-not the pill.

Is pharmacogenetic testing covered by the NHS?

The NHS offers targeted testing for specific high-risk drugs like thiopurines and 5-fluorouracil in cancer care. Broader testing isn’t yet routine in primary care, but pilots are underway. Private tests cost around £250 and are sometimes covered by private health insurance if recommended by a specialist.

What should I do if my doctor ignores my genetic test results?

Request a referral to a clinical pharmacologist or hospital pharmacy team. They specialize in interpreting genetic data and can work with your GP to adjust your treatment. Bring printed copies of the results and the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines for your gene-drug pair. Many doctors don’t know how to use the data-but they’ll listen if a specialist says it’s necessary.

12 Comments

Write a comment

More Articles

Online Lasix Prescription: Insights and Essential Guide

This article provides a comprehensive guide to obtaining a Lasix prescription online, along with detailed insights into the medication itself. It covers the medical and side effects, drug interactions of Lasix and its active substance, Furosemide. Furthermore, it offers guidance on the most common dosages and recommendations for those considering Lasix as a treatment option. It aims to equip readers with the knowledge they need to make informed decisions about using Lasix safely and effectively.

Rheumatoid Arthritis Medications: DMARD and Biologic Interactions

Rheumatoid arthritis treatment relies on DMARDs and biologics to stop joint damage. Methotrexate remains first-line, but biologics and JAK inhibitors offer stronger control for severe cases-with trade-offs in cost, side effects, and long-term safety.

Himanshu Singh

January 24, 2026 AT 05:58Man, this hit home. My dad died from a bad reaction to warfarin-no one ever asked about his side effects with penicillin in the 70s. Turns out, he was a slow CYP2C9 metabolizer. We got tested after. Scary how much we just guess with meds.

Genes don’t lie. And neither does your family’s medical history. If your grandma couldn’t handle antidepressants, don’t brush it off. It’s not "just bad luck." It’s biology.

Also, generics? Sure they’re cheaper-but if your body’s wired differently, you’re playing Russian roulette with fillers. I switched from one generic sertraline to another and nearly went to the ER. Turns out, the coating changed the release rate. My CYP2D6 test confirmed I’m a slow metabolizer. No doctor ever asked. 😔