What Are Zoonotic Diseases?

Most people think of colds or the flu as things you catch from other people. But zoonotic diseases are infections that jump from animals to humans. They’re not rare. In fact, about 60% of all known infectious diseases in humans started in animals. And 75% of new diseases that have emerged in the last 20 years came from wildlife or livestock. Rabies, Lyme disease, salmonella from pet turtles, bird flu, even HIV-these all began in animals before making the leap to people.

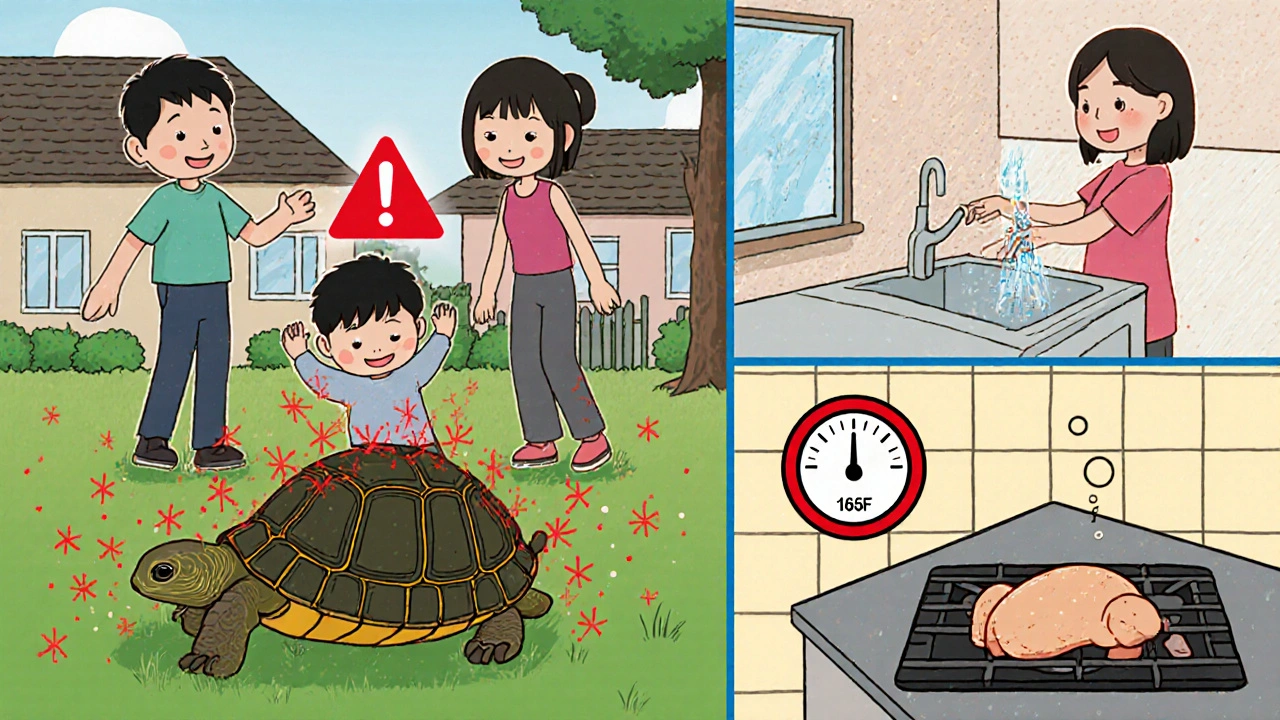

The word itself comes from Greek: zoon means animal. These diseases aren’t just a problem in faraway places. They show up in backyards, farms, pet stores, and even your kitchen. A child gets sick after handling a pet reptile. A hunter develops a fever after butchering a deer. A farmer gets pneumonia from breathing in dust from infected birds. These aren’t accidents. They’re predictable outcomes of how we live with animals-and sometimes, how we ignore the risks.

How Do These Diseases Jump from Animals to People?

Zoonotic diseases don’t just randomly appear in humans. They follow clear paths. There are five main ways they spread:

- Direct contact: Touching, petting, or being bitten by an infected animal. Rabies from a dog bite, or cat scratch disease from a kitten’s claw, are classic examples.

- Indirect contact: Touching something an animal has contaminated-like a cage, soil, or water. Salmonella spreads this way when you touch a turtle’s tank and then eat without washing your hands.

- Vector-borne: Bites from ticks, mosquitoes, or fleas. Lyme disease comes from tick bites. West Nile virus comes from mosquitoes. These insects pick up the pathogen from an animal and pass it on to you.

- Foodborne: Eating undercooked meat, raw milk, or eggs from infected animals. Campylobacter and E. coli outbreaks often trace back to poultry or beef. The CDC says 1 in 6 Americans get sick from contaminated food every year-and many of those cases are zoonotic.

- Waterborne: Drinking or swimming in water polluted by animal waste. Giardia, a parasite that causes severe diarrhea, often spreads this way near farms or wildlife areas.

It’s not just about being around animals. It’s about how you interact with them. A 2022 survey found that 23% of pet owners had been exposed to a zoonotic disease-and 67% didn’t know how to prevent it. That’s not ignorance. That’s lack of clear, practical guidance.

Common Zoonotic Diseases You Should Know

Some zoonotic diseases are rare. Others are everywhere. Here are the most common ones you’re likely to encounter:

- Salmonella: Found in reptiles, birds, and livestock. Symptoms: diarrhea, fever, stomach cramps. Can be deadly for young kids and the elderly. A family in Wisconsin got sick after getting pet turtles. The 2-year-old had to be hospitalized.

- Rabies: Almost always fatal once symptoms appear. Spread by bites from infected dogs, bats, raccoons, or foxes. The good news? It’s 100% preventable with vaccines-for pets and people.

- Lyme disease: Carried by ticks that feed on deer and mice. Early signs: bull’s-eye rash, fever, fatigue. Left untreated, it can damage joints, the heart, and the nervous system.

- Ringworm: Not a worm. It’s a fungal infection that spreads from pets (especially cats) to humans. Causes itchy, red, circular rashes. Very common in households with pets.

- Psittacosis: From birds like parrots and chickens. Causes pneumonia-like symptoms. A poultry farmer in Minnesota spent 14 days in the hospital after catching it from his flock.

- Toxoplasmosis: From cat feces. Pregnant women are warned to avoid litter boxes because it can harm the fetus.

- Brucellosis: From raw milk or undercooked meat from infected cows or goats. Causes fever, joint pain, fatigue. Still common in rural areas where raw dairy is sold.

And then there’s the scary stuff-Ebola, Nipah virus, bird flu. These don’t spread easily between people, but when they jump from animals, they can be deadly. In Kerala, India, 17 people died from Nipah virus in just a few months because the outbreak wasn’t caught early enough.

Why Is This Happening More Often?

It’s not random. We’re creating the perfect conditions for these diseases to spread.

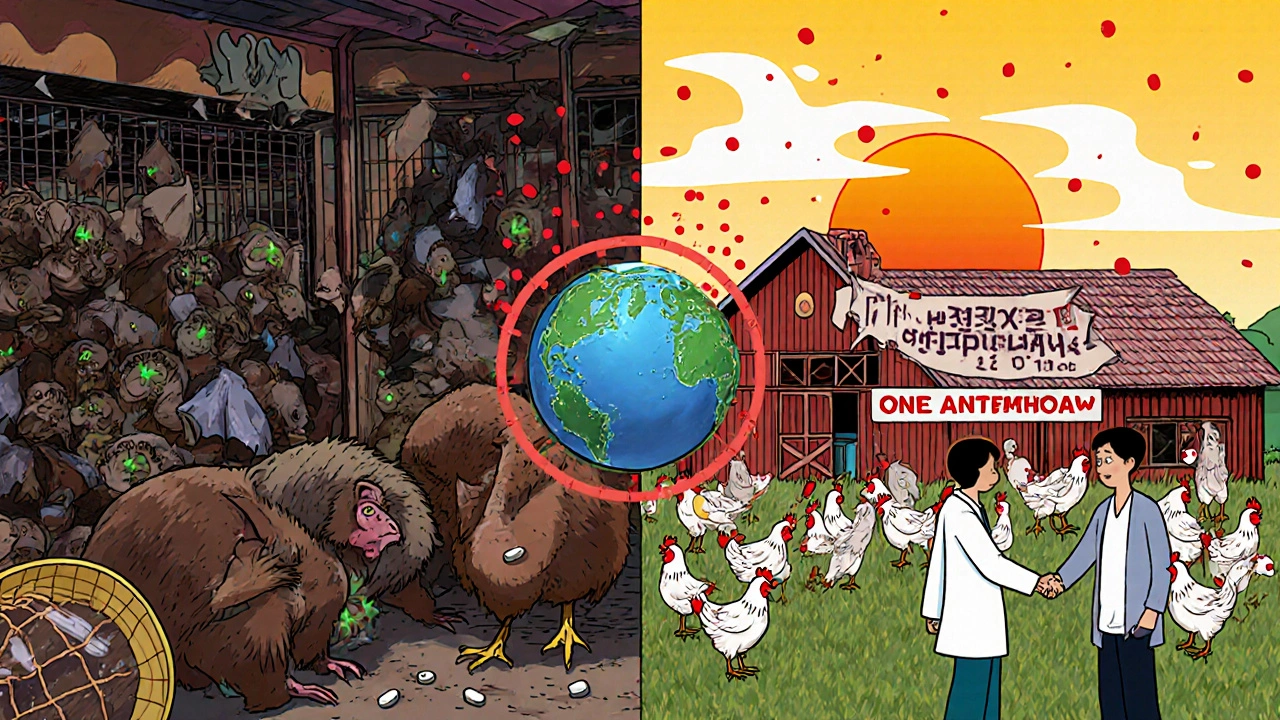

Deforestation and land development push wild animals into human spaces. In the Amazon, farmers clearing land for cattle are coming into contact with bats that carry viruses. In Southeast Asia, wildlife markets pack monkeys, civets, and pangolins into cages-perfect for viruses to mix and mutate. According to experts, land-use changes like this are responsible for over 30% of new zoonotic outbreaks.

Climate change is making things worse. Ticks that once lived only in southern states are now found in Canada. Mosquitoes carrying dengue and Zika are moving into new areas. By 2050, the area suitable for Lyme disease in North America could grow by 45%.

And then there’s our food system. Factory farms cram thousands of animals together, creating breeding grounds for superbugs. Antibiotics are overused in livestock, leading to drug-resistant strains of salmonella and E. coli. The CDC says 20% of antibiotic-resistant infections in the U.S. come from animals.

It’s not that animals are dangerous. It’s that we’ve disrupted the balance. As Jane Goodall said, "Our disrespect for wild animals and their habitats has created the perfect conditions for diseases to jump from animals to humans."

How to Protect Yourself and Your Family

Prevention isn’t complicated. It’s about habits. Here’s what actually works:

- Wash your hands: Always after touching animals, cleaning cages, handling pet food, or using the bathroom. Soap and 20 seconds of scrubbing cuts transmission by 90%.

- Cook meat properly: Poultry must reach 165°F. Ground beef should hit 160°F. Use a thermometer. Don’t guess.

- Avoid wild animals: Don’t touch or feed raccoons, bats, or deer. Don’t bring home baby wildlife. They’re often sick and carry parasites.

- Protect against ticks and mosquitoes: Wear long pants in grassy areas. Use EPA-approved repellents. Check for ticks after being outside.

- Don’t kiss your pets: Their mouths carry bacteria that can make you sick. Same goes for letting them lick your face.

- Keep pets healthy: Vaccinate dogs and cats. Use flea and tick preventatives. Get regular vet checkups.

- Be smart with reptiles and amphibians: Don’t let them roam your kitchen. Wash hands immediately after handling. Never let kids under 5 touch them.

- Don’t drink raw milk: Pasteurization kills harmful bacteria. Raw milk is a major source of brucellosis and E. coli.

And if you work with animals-veterinarian, farmer, wildlife worker-you need more than common sense. You need training. A 2022 study found that 68% of doctors in the U.S. can’t recognize the early signs of zoonotic diseases. That’s dangerous. If you’re sick after handling animals, tell your doctor. Say: "I think it might be zoonotic."

Why One Health Matters

You can’t fix this problem by treating sick people alone. You have to protect animals and the environment too. That’s the idea behind One Health. It’s the understanding that human health, animal health, and ecosystem health are all connected.

Uganda cut rabies deaths by 92% by vaccinating 70% of its dogs. That’s One Health in action: protect the animals, protect the people. In the U.S., the CDC has launched $25 million in grants to train doctors, vets, and environmental scientists together. Europe has laws requiring farms to report disease outbreaks. The U.S. doesn’t. Only 28 states require all zoonotic diseases to be reported.

Global health experts say investing $10 billion a year in One Health programs could prevent 70% of future pandemics. The return? $100 for every $1 spent. That’s not just smart public health. It’s economic sense.

But progress is slow. Only 38% of countries have systems that link human and animal health agencies. Without that connection, outbreaks go unnoticed until it’s too late.

What’s Next?

The threat isn’t going away. Climate change, habitat loss, and global travel mean more diseases will jump from animals to people. The next big outbreak could come from a bat in the Congo, a pig in Vietnam, or a chicken in Iowa.

But we’re not powerless. We can demand better food safety rules. We can support wildlife conservation. We can make sure our pets are vaccinated. We can teach our kids to wash their hands after playing with the dog.

It’s not about fearing animals. It’s about respecting the boundaries between species. The same actions that protect you from salmonella also protect your cat from fleas. The same rules that keep your farm safe also keep your community healthy.

Zoonotic diseases remind us: we’re not separate from nature. We’re part of it. And when we damage that balance, we pay the price-in sickness, in death, in cost. The solution isn’t a magic pill. It’s better habits, better policies, and better awareness. Start with your hands. Then move to your community. The next outbreak might be stopped before it even begins.

Can you get zoonotic diseases from pet birds?

Yes. Birds like parrots, pigeons, and chickens can carry psittacosis, a bacterial infection that causes pneumonia-like symptoms in humans. You can catch it by breathing in dust from their droppings or feathers. Symptoms include fever, chills, headache, and cough. It’s treatable with antibiotics, but can require hospitalization. Always wash your hands after cleaning bird cages and avoid letting birds near your face.

Are reptiles safe as pets?

Reptiles like turtles, lizards, and snakes commonly carry salmonella, even if they look healthy. The CDC advises against keeping them as pets for children under 5, pregnant women, or people with weak immune systems. Always wash hands thoroughly after handling them or their tanks. Never let them roam freely in kitchens or dining areas. A 2023 study found that 100% of campylobacteriosis cases linked to reptiles involved direct contact with the animal or its environment.

Can you get rabies from a bat?

Yes. Bats are the leading cause of rabies deaths in the U.S. today. You don’t need to be bitten-rabies can spread if bat saliva gets into your eyes, nose, mouth, or an open wound. If you find a bat in your home, don’t touch it. Call animal control. If you wake up and find a bat in your room, assume you were exposed and seek medical help immediately. Rabies is 100% preventable with post-exposure shots-but 100% fatal once symptoms start.

Do I need to worry about zoonotic diseases if I don’t have pets?

Absolutely. You don’t need pets to be at risk. Eating undercooked meat, drinking raw milk, swimming in lakes near farms, or even walking in wooded areas where ticks live can expose you. Lyme disease, E. coli, and giardia are all common zoonotic infections that come from the environment-not pets. The biggest risk isn’t your dog. It’s your dinner, your water, and the bugs in your backyard.

How do I know if my pet is carrying a zoonotic disease?

Many infected animals show no symptoms. A dog with salmonella might act perfectly fine. A cat with toxoplasmosis may seem normal. That’s why prevention matters more than waiting for signs. Regular vet checkups, parasite control, and keeping your pet’s environment clean are your best defenses. If your pet has diarrhea, vomiting, or unusual behavior, tell your vet you’re concerned about zoonotic risks. Early testing can prevent human illness.

Is it safe to feed my pet raw food?

No. Raw pet food (meat, bones, organs) is a major source of salmonella and E. coli for both pets and people. The FDA and CDC strongly warn against it. Pets can shed these bacteria in their feces for weeks-even if they don’t get sick. Handling raw pet food puts you at risk. If you choose to feed raw, wash hands and surfaces immediately after, and never let your pet lick your face. But the safest choice? Cooked, commercial pet food.

15 Comments

Write a comment

More Articles

Osteoarthritis of the Hip: How Weight Loss Can Preserve Your Joint and Reduce Pain

Weight loss isn't just about appearance - for hip osteoarthritis, losing 10% of your body weight can dramatically reduce pain and delay surgery. Learn how diet, exercise, and realistic goals can preserve your joint.

Opioid Addiction and Trauma: Understanding the Unseen Link

Opioid addiction and trauma are often intertwined, with past emotional or physical pain contributing to dependency. This connection highlights the importance of addressing the underlying trauma in addiction treatment. Steps like trauma-informed care and personalized therapy can aid in recovery. Understanding this link is crucial for both individuals struggling with addiction and those supporting them.

Manufacturing Transparency: How to Access FDA Inspection Records

Understand how FDA inspection records work, what manufacturers must disclose, and how internal audits differ from required quality investigations. Learn what triggers inspections, how to respond to Form 483, and why remote assessments are changing compliance.

Deirdre Wilson

November 25, 2025 AT 22:30I had a turtle as a kid and never washed my hands after playing with it. Still here. 🐢😅 But yeah, this post really laid it out-zoonotic stuff isn’t just ‘wild animal’ drama. It’s in our kitchens, our backyards, our pet stores. We act like animals are dirty, but we’re the ones ignoring the basics.