When you pick up a prescription, you might see two different dates on the label: one that says expiration date, and another that says beyond-use date. They look similar, but they’re not the same. Confusing them can lead to wasted medicine, lost money, or even health risks. Understanding the difference isn’t just technical-it’s practical. If you’re taking a compounded medication, like a custom liquid for a child or a dye-free pill because of allergies, you need to know exactly when it’s safe to use. This isn’t about guessing. It’s about knowing what the dates mean, who sets them, and why they’re so different.

What Is a Manufacturer Expiration Date?

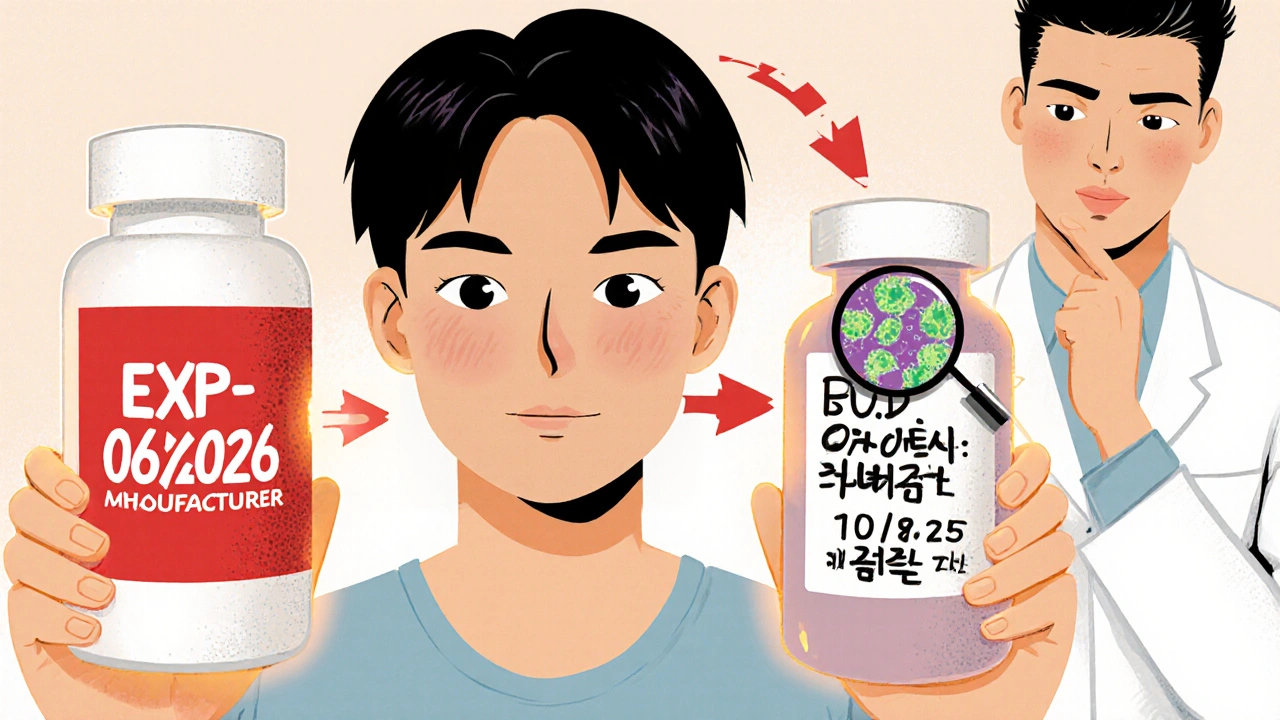

An expiration date is stamped on every FDA-approved drug you buy at the pharmacy. It’s printed on the bottle, box, or blister pack. This date isn’t arbitrary. It’s the result of months, sometimes years, of stability testing by the manufacturer. The company puts the medicine under controlled heat, humidity, and light to see how long it stays potent and safe. The FDA requires this testing before a drug hits the market. The manufacturer guarantees that the medication will work as labeled up to that date-even if the container is opened. For example, if a bottle of amoxicillin says Expiration: 06/2026, that means the drug is expected to retain at least 90% of its labeled strength until June 2026, assuming it’s stored properly-usually at room temperature, away from moisture and direct sunlight. Even if you opened it last year, the expiration date still applies. The FDA has tested over 100 drugs and found that many still work well past their expiration dates under ideal conditions. But that’s lab conditions. Real life? Your medicine might sit in a hot bathroom, a sunlit kitchen counter, or a car glovebox. That’s why the FDA doesn’t recommend using drugs past their expiration date. The guarantee ends there.What Is a Beyond-Use Date?

A beyond-use date (BUD) is something you’ll only see on medications that have been changed after leaving the manufacturer. That includes compounded drugs-medicines made by a pharmacy to fit a patient’s unique needs. Maybe your child can’t swallow pills, so the pharmacy mixes a liquid version. Maybe you’re allergic to a dye in the commercial tablet, so they make you a dye-free version. Or maybe a hospital pharmacist adds antibiotics to an IV bag. Once the original packaging is opened, the product is altered, and the manufacturer’s expiration date no longer applies. The BUD is set by the pharmacist, following guidelines from the United States Pharmacopeia (USP). It’s not a guess. It’s based on science: how stable the ingredients are, whether the formulation contains water (which invites bacteria), how it’s stored, and whether it’s sterile or non-sterile. For example, a simple oral liquid made from two powdered ingredients might get a BUD of 30 days at room temperature. But if that same liquid contains water and isn’t refrigerated, the BUD drops to just 14 days. Sterile IV bags? Those might last up to 48 hours if refrigerated, or only 6 hours if left out. Unlike expiration dates, BUDs start from the day the pharmacy makes the medicine-not the day the drug was manufactured. So even if the original powder inside the liquid had an expiration date of 2028, the BUD on your bottle might say BUD: 10/15/2025. That’s because the pharmacist didn’t just hand you the powder. They mixed, measured, and bottled it. That process changes everything.Why the Dates Are So Different

The key difference comes down to control. Manufacturers produce thousands of identical bottles under sterile, consistent conditions. They test each batch. They seal the containers in ways that protect the medicine from air and moisture. Their expiration dates reflect that level of control. Pharmacies? They’re making one-off doses. A compounding pharmacist might mix a liquid for one patient, using a vial of powder that’s been open for months. They don’t have the same lab equipment or quality control. Even the air in the room matters. That’s why BUDs are shorter. They’re conservative by design. They’re not saying the medicine will definitely go bad on that date. They’re saying: after this date, we can’t guarantee it’s safe or effective. Take a common example: thyroid medication. If you get a commercial tablet, it might expire in 2027. But if your pharmacist compounds it into a liquid because you can’t swallow pills, the BUD might be just 6 months from the day they made it. That’s not a mistake. That’s science. The liquid form lacks the preservatives and stabilizers in the tablet. It’s more vulnerable. And if you forget to refrigerate it? The clock ticks even faster.

What Happens If You Use Medicine Past Either Date?

Using a drug past its expiration date might mean it’s less effective. If your antibiotic is only 70% potent, it might not kill all the bacteria. That can lead to longer illness or antibiotic resistance. In rare cases, degraded chemicals can become toxic. For example, tetracycline antibiotics can break down into substances that harm the kidneys if used after expiration. Beyond-use dates carry similar risks-but often higher ones. Compounded medications don’t have the same preservatives as commercial drugs. A liquid that’s been sitting for 8 weeks might grow bacteria or mold, even if it looks fine. That’s not theoretical. In 2012, a fungal meningitis outbreak killed 64 people and sickened over 750 across 20 states. The cause? Compounded steroid injections that were contaminated and had been stored past their BUD. The FDA doesn’t track how many people get sick from expired or improperly dated meds, but pharmacists know it happens. That’s why they’re so strict. It’s not about fear. It’s about preventing something that’s already happened.How to Tell Them Apart

Here’s how to spot the difference:- Expiration date: Appears on the original manufacturer’s packaging. Usually says “EXP” or “Expiration Date” followed by a month/year or full date (e.g., “EXP 08/2025”).

- Beyond-use date: Appears on the pharmacy’s label. Usually says “BUD” or “Beyond Use Date.” It’s often handwritten or printed on a sticker over the original label. It’s always tied to the day the pharmacy prepared it.

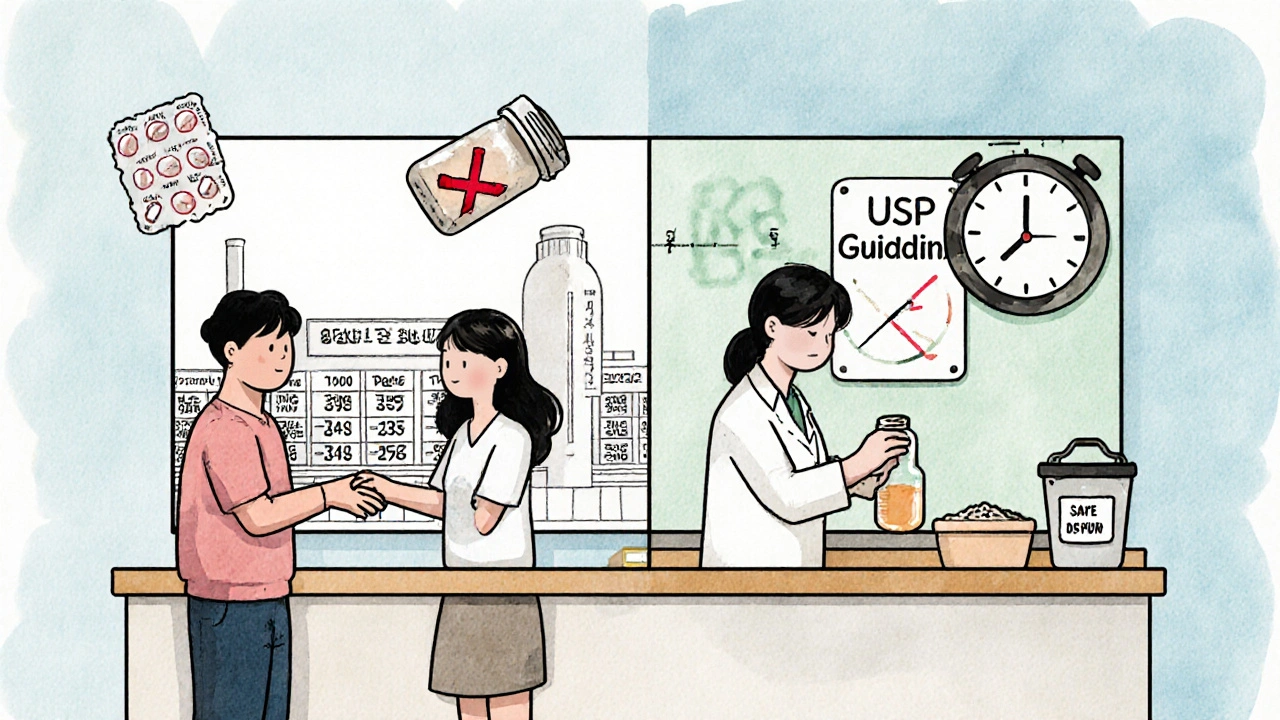

What Patients Should Do

You don’t need to be a pharmacist to use this right. Here’s what to do:- Always check both dates. When you get your medicine, look for the BUD on the pharmacy label. Don’t assume it’s the same as the expiration date on the bottle.

- Follow storage instructions. If the BUD label says “Refrigerate,” keep it in the fridge. If it says “Store at room temperature,” don’t put it in the bathroom. Humidity kills compounded meds faster.

- Ask questions. If you’re unsure which date to follow, call the pharmacy. Say: “Is this a compounded medication? What’s the beyond-use date?” Most pharmacists will explain it without judgment.

- Don’t use it past the date. Even if it looks fine. Even if you have a few pills left. The risk isn’t worth it.

- Return expired meds. Most pharmacies offer free take-back programs. Don’t throw them in the trash or flush them. Ask your pharmacist how to dispose of them safely.

Why This Matters for Compounded Medications

Compounded medications aren’t rare. About 8 million people in the U.S. rely on them every year. They’re essential for patients with allergies, rare conditions, or kids who need flavors and doses that don’t exist commercially. But they’re also more expensive-often 2 to 5 times the cost of a regular pill. And because BUDs are short, many patients throw away unused medicine before finishing their course. A 2022 survey found that 68% of patients on compounded meds had to toss some because the BUD ran out before they finished treatment. That’s not just wasteful-it’s costly. One patient in Birmingham told me they paid $120 for a compounded thyroid liquid, only to discard half of it after six months because the BUD expired. The original tablet would’ve cost $15 and lasted a year. That’s why understanding BUDs isn’t just about safety. It’s about money, too.What’s Changing in the Future

The USP is updating its guidelines for BUDs in 2025 and 2026. Some high-risk compounded medications may get even shorter BUDs-up to 30% shorter than before. That’s because regulators are seeing more cases of contamination and potency loss. The goal isn’t to make life harder for patients. It’s to make sure every compounded dose is safe. Meanwhile, the FDA continues to crack down on pharmacies that assign BUDs too loosely. In 2022, they issued 27 warning letters to compounding pharmacies for improper dating. That’s up from 19 in 2021. The message is clear: BUDs aren’t suggestions. They’re legal requirements.Final Takeaway

Expiration dates and beyond-use dates aren’t interchangeable. One is a manufacturer’s promise. The other is a pharmacist’s safety net. If you’re taking a commercial drug, follow the expiration date. If you’re taking something mixed by a pharmacy, follow the BUD-no exceptions. Don’t rely on looks, smell, or intuition. If the date’s passed, it’s time to replace it. Your health isn’t worth the risk.Is it safe to use medicine after the expiration date?

The FDA doesn’t recommend using any medication past its expiration date. While some drugs may still be potent years later under ideal storage, real-world conditions-like heat, moisture, and light-can degrade them. Using expired medicine risks reduced effectiveness or, in rare cases, harmful breakdown products. Always follow the date on the label.

Can I use a compounded medication after its beyond-use date if it still looks fine?

No. Even if the liquid looks clear or the pill hasn’t changed color, compounded medications can become contaminated or lose potency without visible signs. They often lack preservatives, making them more vulnerable to bacteria or mold. Using it past the BUD could lead to infection or treatment failure.

Why does my compounded medicine have a shorter date than the original bottle?

Because the pharmacy changed the product. The original expiration date only applies to the unopened, unaltered medicine as made by the manufacturer. Once a pharmacist mixes, dilutes, or repackages it, the original guarantee no longer stands. The beyond-use date is based on how stable the new formulation is under pharmacy storage conditions.

Who sets the beyond-use date-the pharmacy or the manufacturer?

The pharmacy sets the beyond-use date, following USP guidelines. The manufacturer’s expiration date applies only to their original, unaltered product. Once the pharmacy alters the medication-by compounding, repackaging, or reconstituting-it’s no longer under the manufacturer’s control, so they can’t guarantee its safety past their date.

Do I need to refrigerate all compounded medications?

Not all, but many do. Water-based liquids, creams, and suspensions often require refrigeration because they’re more prone to bacterial growth. Always follow the storage instructions on the pharmacy label. If it says “refrigerate,” keep it cold. If it says “room temperature,” avoid the bathroom or near the stove.

Can I ask my pharmacy to extend the beyond-use date?

No. Beyond-use dates are based on scientific standards, not convenience. Pharmacists can’t legally extend them, even if you have leftover medicine. If you need more, you’ll need a new prescription and a new BUD. This protects your safety.

9 Comments

Write a comment

More Articles

Osteoarthritis of the Hip: How Weight Loss Can Preserve Your Joint and Reduce Pain

Weight loss isn't just about appearance - for hip osteoarthritis, losing 10% of your body weight can dramatically reduce pain and delay surgery. Learn how diet, exercise, and realistic goals can preserve your joint.

Joseph Peel

November 17, 2025 AT 14:42The distinction between expiration dates and beyond-use dates is critical, and this post nails it. Manufacturers test under controlled environments-pharmacies don’t. That’s not negligence; it’s reality. If you’re on a compounded liquid, treat the BUD like a bomb timer. Miss it, and you’re gambling with efficacy, not just safety.