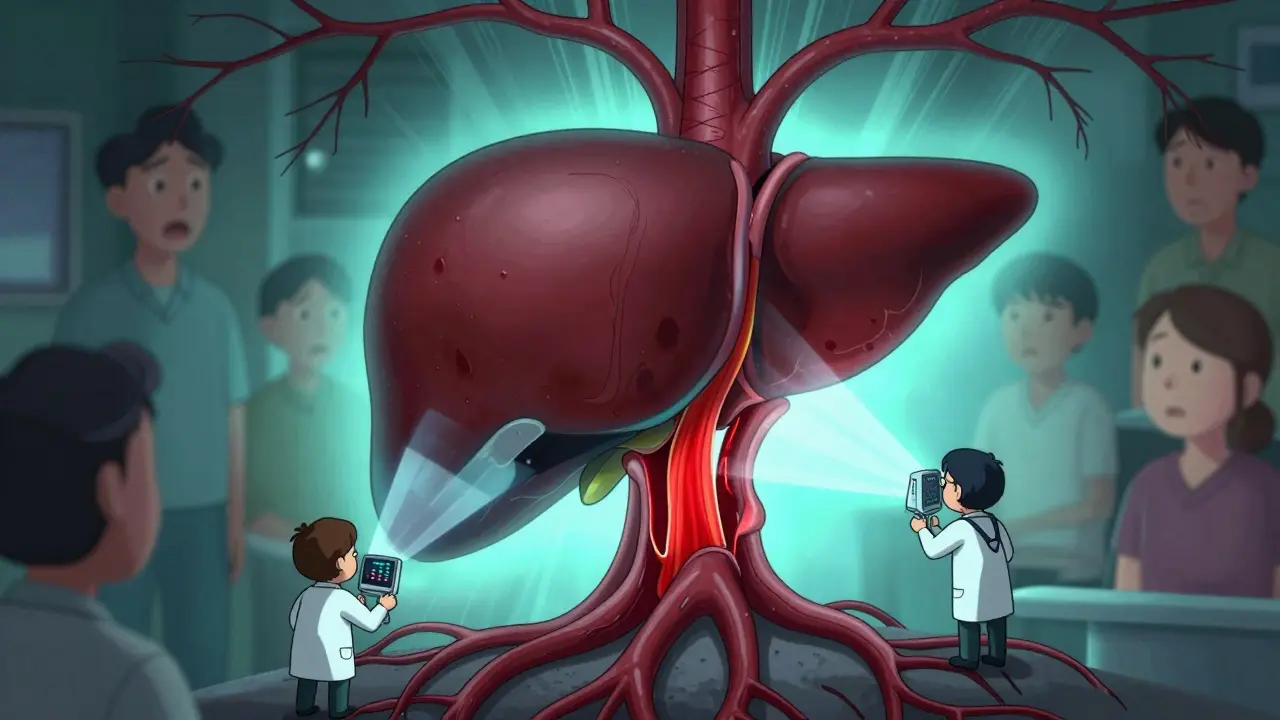

What Is Portal Vein Thrombosis?

Portal vein thrombosis (PVT) happens when a blood clot blocks the portal vein - the main vessel that carries blood from your intestines to your liver. It’s not rare, especially in people with liver disease, cancer, or inherited blood clotting disorders. The clot can be partial or complete, and it can show up suddenly (acute) or develop slowly over time (chronic). Acute PVT is more treatable. If left alone, it can lead to serious problems like intestinal damage, worsening liver scarring, or even life-threatening bleeding.

First described in 1868, PVT follows Virchow’s triad: slow blood flow, damaged vessel walls, and blood that clots too easily. Today, we know that cirrhosis is the most common cause - but not the only one. Other triggers include abdominal infections, pancreatitis, recent surgery, or even pregnancy. In people without liver disease, up to 30% have an underlying clotting disorder like Factor V Leiden. That’s why testing for these conditions matters.

How Is Portal Vein Thrombosis Diagnosed?

Ultrasound is the first and most important test. It’s quick, safe, and detects PVT with 89-94% accuracy. A Doppler ultrasound doesn’t just show the clot - it shows if blood is still flowing through the vein. If the portal vein looks blocked and there’s no flow, that’s a clear sign of PVT. In some cases, the body builds new tiny blood vessels around the clot, a pattern called cavernous transformation. That usually means the clot has been there for a while.

If the ultrasound is unclear, doctors turn to CT or MRI scans with contrast. These give a detailed 3D view of the portal system and help decide how much of the vein is blocked. Is it 50%? 90%? Completely closed? The level of blockage affects treatment choices. A clot that’s just started (within two weeks) has a much better chance of dissolving than one that’s been there for months.

But diagnosis isn’t just about imaging. You also need to know why it happened. That means checking liver function with Child-Pugh and MELD scores, screening for varices (swollen veins in the esophagus) with an endoscopy, and running blood tests for clotting disorders. Skipping these steps can lead to dangerous mistakes - like giving anticoagulants to someone who’s about to bleed.

Why Anticoagulation Is the Standard Treatment

For years, doctors were unsure whether to treat PVT with blood thinners - especially in cirrhotic patients. But the data now is clear: anticoagulation saves lives. A 2023 study showed that patients treated early had an 85% five-year survival rate. Those who weren’t treated? Far worse.

The goal isn’t just to prevent the clot from getting bigger. It’s to dissolve it, restore blood flow, and stop complications like intestinal ischemia or worsening portal hypertension. Recanalization - when the vein reopens - happens in 65-75% of cases if treatment starts within six months. Delay treatment, and that number drops to 16-35%.

Guidelines from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) now say: if you don’t have a high bleeding risk, treat PVT with anticoagulation - even if you have cirrhosis. That’s a big shift from just five years ago.

Which Blood Thinners Work Best?

Not all anticoagulants are the same for PVT. The choice depends on your liver health and whether you have other risks.

Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) - like enoxaparin - is often the first choice, especially in cirrhosis. It’s given as a daily injection. Dosing is based on weight: 1 mg/kg twice a day or 1.5 mg/kg once daily. It’s preferred because it’s easier to control than warfarin in people with liver disease. Studies show it leads to recanalization in 55-65% of Child-Pugh A/B patients.

Warfarin (a VKA) used to be the go-to. But it’s tricky. It needs constant blood tests (INR checks) to stay between 2.0 and 3.0. In cirrhotic patients, it’s less effective - only 30-40% recanalization - and harder to manage because the liver can’t make clotting factors properly.

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) - like rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran - are now preferred for non-cirrhotic patients. They don’t need regular blood tests. In studies, rivaroxaban achieved 65% recanalization, apixaban 65%, and dabigatran 75%. They’re simpler, safer, and more effective than warfarin in people with healthy livers.

But DOACs aren’t for everyone. They’re not approved for Child-Pugh C cirrhosis. The FDA warns against using them in severe liver impairment. For Child-Pugh B patients, newer data from the 2024 AASLD update shows DOACs are now considered safe - as long as you’re monitored closely.

When Not to Use Anticoagulation

Anticoagulation isn’t risk-free. In cirrhotic patients, bleeding is the biggest concern. About 5-12% of these patients will have a major bleed while on blood thinners. Most of those bleeds come from varices - swollen veins in the esophagus.

That’s why endoscopic screening is mandatory before starting anticoagulation in anyone with cirrhosis. If varices are found, they need to be treated with band ligation first. At UCLA, this step cut major bleeding from 15% to just 4%.

Anticoagulation is also avoided if:

- You’ve had a variceal bleed in the last 30 days

- You have uncontrolled ascites (fluid in the belly)

- Your liver function is Child-Pugh C (severe cirrhosis)

In these cases, the risk of bleeding outweighs the benefit. Some doctors still debate whether to treat asymptomatic PVT in cirrhotic patients without cancer. But the trend is clear: if you’re stable and have a chance at recanalization, treat it.

What About Surgery or Other Options?

Anticoagulation is first-line. But if it fails, or if the clot is massive and causing intestinal damage, other options exist.

TIPS (Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt) creates a tunnel inside the liver to reroute blood. It works in 70-80% of cases. But it comes with risks - 15-25% of patients develop hepatic encephalopathy (brain fog from liver toxins). It’s not a cure for PVT, just a way to manage pressure.

Percutaneous thrombectomy uses a catheter to physically break up the clot. It gives immediate results in 60-75% of cases. But it’s only available at major transplant centers. It’s expensive, invasive, and not for everyone.

Surgical shunts are rarely used now. They’re more dangerous and have longer recovery times.

For transplant candidates, treating PVT is critical. At UCSF, anticoagulation cut the number of patients disqualified from transplant lists from 22% to just 8%. Without treatment, a clot can make you ineligible for a new liver.

How Long Do You Need to Stay on Blood Thinners?

It depends on why you got the clot.

If it was triggered by something temporary - like surgery or infection - and that cause is gone, you usually take anticoagulants for 6 months. After that, you stop, as long as the vein reopened and no clotting disorder was found.

If you have a genetic clotting disorder (like Factor V Leiden), you’ll likely need lifelong treatment. The same goes for people with active cancer. For those with cirrhosis and no clear trigger, treatment is often long-term - sometimes indefinite - because the risk of new clots never fully disappears.

Follow-up imaging at 3 and 6 months is standard. If the vein is still blocked after 6 months of treatment, you may need to keep anticoagulation going, even if you’re not sure why.

Real-World Challenges and Success Stories

Managing PVT isn’t just about picking the right drug. It’s about coordination. At Mayo Clinic, patients treated within 30 days of diagnosis had a 78% recanalization rate. Those treated later? Only 42%. Delay matters.

At Johns Hopkins, a team approach - involving hepatologists, radiologists, and transplant surgeons - cut complications by 35%. One patient, a 58-year-old with cirrhosis and a new PVT, had varices treated with banding, then started on apixaban. Six months later, his portal vein was fully open. He’s now on the transplant list.

But failures happen too. At Massachusetts General, 22% of patients who presented with intestinal ischemia died. Most of them had waited weeks to get diagnosed. Early detection saves lives.

Community doctors still struggle. Only 35% of general gastroenterologists feel confident managing PVT anticoagulation. That’s why resources like the American Liver Foundation’s patient toolkit and AASLD’s case discussions are so important.

What’s Next for PVT Treatment?

The future is promising. In 2023, the FDA approved andexanet alfa - a drug that can reverse the effects of rivaroxaban and apixaban in emergencies. That’s a game-changer for bleeding control.

New drugs like abelacimab are in early trials. They target clotting differently and might be safer for liver patients. The PROBE trial showed DOACs are as safe as LMWH in Child-Pugh A/B patients - and that’s changing practice.

By 2025, DOACs could be used in 75% of non-cirrhotic PVT cases and 40% of compensated cirrhotic cases. Genetic testing is also becoming part of routine care. If you have Factor V Leiden, your chance of recanalization with long-term anticoagulation jumps to 80%.

One thing won’t change: anticoagulation remains the cornerstone. Whether you’re a young person with a clotting disorder or an older adult with cirrhosis, timely, tailored treatment makes all the difference.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can portal vein thrombosis go away on its own?

Sometimes, yes - but rarely. Small, partial clots may dissolve without treatment, especially if the trigger (like an infection) resolves. But in most cases, especially with complete blockage or underlying liver disease, the clot won’t disappear without anticoagulation. Waiting increases the risk of chronic PVT, which is harder to treat and can lead to long-term complications like portal hypertension or liver failure.

Is anticoagulation safe if I have cirrhosis?

It can be - but only if you’re carefully selected. For Child-Pugh A or B cirrhosis, anticoagulation is now recommended if you have acute PVT, especially if you’re not actively bleeding. LMWH or DOACs (like apixaban) are preferred. But if you have Child-Pugh C, active bleeding, or uncontrolled ascites, anticoagulation is usually avoided. Always get screened for varices first - treating them reduces bleeding risk by up to 75%.

Do I need lifelong anticoagulation for PVT?

Not always. If your PVT was caused by a temporary issue - like recent surgery or pancreatitis - and you’ve had successful recanalization, 6 months of treatment is usually enough. But if you have a genetic clotting disorder, cancer, or chronic liver disease with no clear trigger, lifelong anticoagulation is often needed. Your doctor will use follow-up scans and blood tests to decide.

Can I take DOACs if I’m on other liver medications?

Most DOACs are safe with common liver meds, but interactions matter. Rivaroxaban and apixaban are processed by the liver and can be affected by drugs like rifampin or certain antifungals. Always tell your doctor what you’re taking - including supplements. DOACs are generally preferred over warfarin because they have fewer interactions, but they’re not risk-free. Your liver function will be monitored closely.

What’s the biggest mistake doctors make with PVT?

Delaying diagnosis and treatment. Many patients are misdiagnosed as having just “abdominal pain” or “worsening cirrhosis.” If you have cirrhosis and new abdominal discomfort, a Doppler ultrasound should be done immediately. Another big mistake is starting anticoagulation without checking for varices. That’s like lighting a match near gasoline - it can trigger fatal bleeding.

How do I know if my anticoagulation is working?

You won’t feel it. The only way to know is through imaging. A follow-up ultrasound or CT scan at 3-6 months will show if the clot has shrunk or disappeared. Blood tests like INR or anti-Xa levels help monitor dose, but they don’t tell you if the clot is resolving. Recanalization is the real goal - not just a number on a lab report.

15 Comments

Write a comment

More Articles

Telehealth Strategies for Monitoring Side Effects in Rural and Remote Patients

Telehealth is transforming how rural and remote patients manage medication side effects. From smart devices to pharmacist-led monitoring, discover how these strategies reduce hospitalizations and save lives in underserved areas.

Alpelisib: Frequently Asked Questions and Expert Answers

I recently explored the topic of Alpelisib, a medication used to treat advanced breast cancer, and gathered some frequently asked questions and expert answers. Alpelisib is specifically designed for patients with PIK3CA gene mutations, and it works by inhibiting the growth and spread of cancer cells. Experts recommend combining Alpelisib with hormone therapy for better results. Common side effects include high blood sugar levels, skin rash, and diarrhea, but these can be managed with appropriate care. If you or a loved one are considering Alpelisib, it's essential to consult with a healthcare professional to determine if it's the right treatment option.

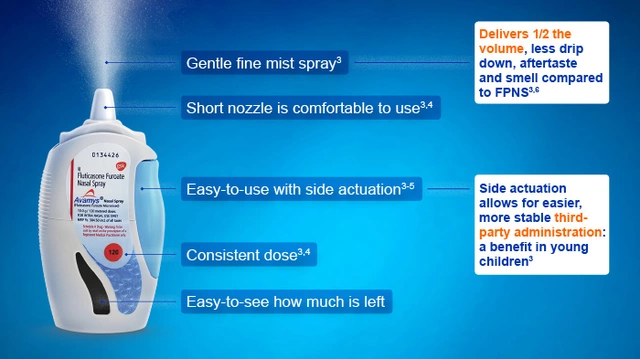

Fluticasone for Travelers: Managing Allergies on the Go

As a traveler, I've found that fluticasone is a game changer in managing allergies on the go. This nasal spray helps reduce inflammation and control common allergy symptoms, allowing me to fully enjoy my trips without constantly sneezing or dealing with itchy eyes. It's easy to pack and use, making it a must-have in my travel essentials. I highly recommend fluticasone for fellow travelers who suffer from allergies, as it makes exploring new places so much more enjoyable. Remember to consult with your doctor before using any medication, especially if you're planning an adventure abroad!

sue spark

December 15, 2025 AT 21:08I never realized how much timing matters with PVT. My uncle waited too long and ended up with chronic issues. Early ultrasound could have changed everything.