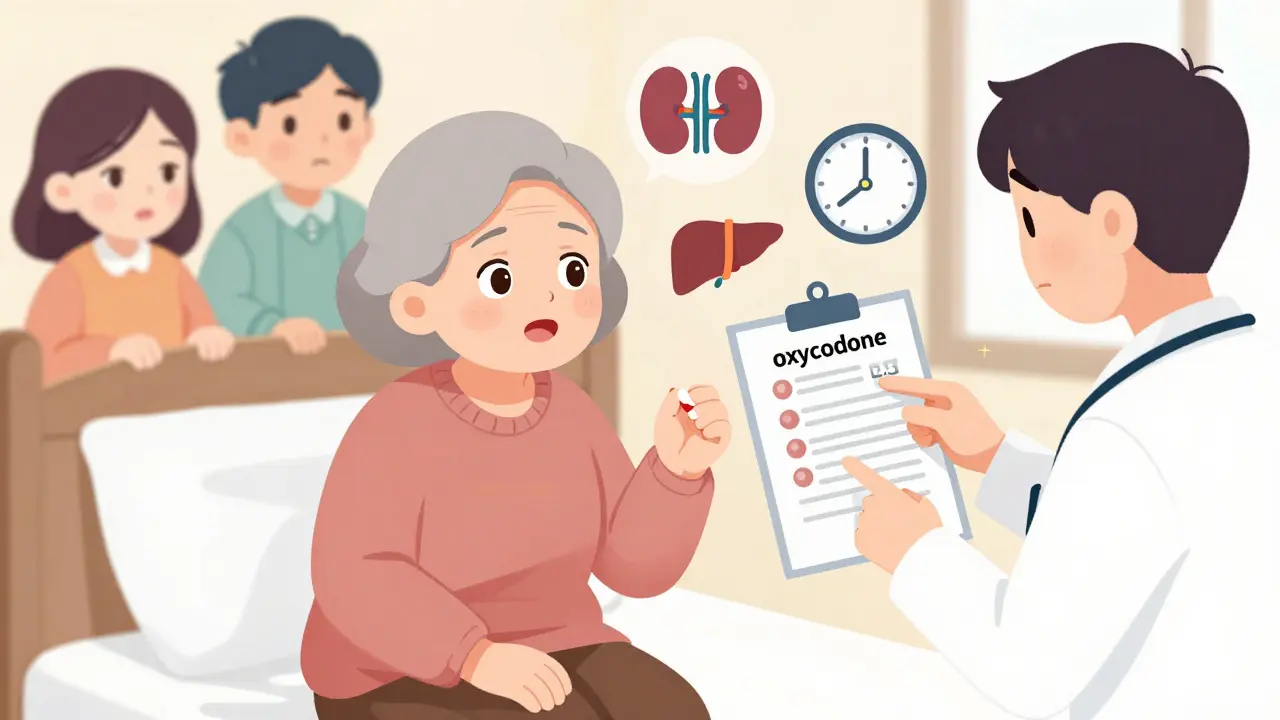

When seniors experience chronic pain, opioids are sometimes the only option that works. But what many don’t realize is that what’s safe for a 40-year-old can be dangerous for someone over 65. The body changes with age-kidneys slow down, liver function declines, and fat distribution shifts. These changes mean drugs like oxycodone or morphine stick around longer and hit harder. That’s why using opioids in older adults isn’t just about picking a pill; it’s about careful, personalized planning.

Why Opioids Are Riskier for Seniors

Older adults are more likely to be on multiple medications. A typical 70-year-old might be taking blood pressure pills, diabetes drugs, antidepressants, and sleep aids. Add an opioid into that mix, and the risks climb fast. Sedation, confusion, falls, and breathing problems become real dangers. A 2023 study in JAMA Network Open found that when strict opioid limits were applied to seniors with cancer, many were switched to tramadol or gabapentin. But those alternatives? They cause dizziness and mental fog in older people, leading to more falls and hospital visits.

Then there’s the issue of metabolism. The liver and kidneys don’t clear drugs as efficiently in seniors. A standard 10 mg dose of oxycodone might be fine for a younger adult, but for someone over 75, it could be too much. That’s why guidelines now say: start at 30% to 50% of the usual adult dose. For many, that means beginning with just 2.5 mg of oxycodone or 7.5 mg of morphine-half of what’s in a standard tablet.

What Opioids Are Safe? What to Avoid

Not all opioids are created equal for seniors. Some are outright dangerous. Meperidine (Demerol) is banned for older adults because its metabolite builds up in the body and can trigger seizures and delirium. Codeine is also off-limits-many seniors lack the enzyme needed to convert it into its active form, making it useless. Others convert it too quickly, leading to overdose.

Tramadol and tapentadol? Use with caution. They carry a risk of serotonin syndrome when mixed with common antidepressants like SSRIs. That’s a rare but life-threatening condition. Methadone is another no-go. Its long half-life and unpredictable metabolism make dosing a guessing game, especially in frail seniors.

On the safer side: oxycodone, hydromorphone, and morphine can still work-if dosed properly. But the real standout is buprenorphine. It’s a partial opioid agonist, meaning it reduces pain without the same level of respiratory depression. A 2024 study in the American College of Osteopathic Family Physicians Journal showed that low-dose transdermal buprenorphine caused no central nervous system side effects when combined with small doses of oxycodone. It also caused less constipation than full opioids, which is huge-constipation is one of the most common reasons seniors stop taking pain meds.

Dosing Rules That Save Lives

There’s no one-size-fits-all dose for seniors. But there are clear rules to follow.

- Start low: Use 30-50% of the standard adult dose for opioid-naïve patients.

- Avoid patches and long-acting pills at first. These deliver steady, uncontrolled doses. If a senior’s metabolism slows unexpectedly, they can overdose.

- Use immediate-release forms first. That way, you can adjust the dose daily based on response.

- Never exceed 40 mg of morphine equivalents (MME) per day unless absolutely necessary. That’s considered a low-dose range for seniors.

- Don’t rush titration. Wait at least 48 hours between dose increases for short-acting opioids like oxycodone.

For those who need even smaller doses, liquid formulations exist. A 1 mg/mL oxycodone elixir allows for precise drops-something a 2.5 mg tablet can’t offer. Pharmacists can compound these if needed.

What About Non-Opioid Options?

Before opioids, try everything else. But not all non-opioid options are safe either.

NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen? They’re risky for seniors. They can cause stomach bleeding, kidney failure, and heart attacks. Use them only for short bursts-no more than 1-2 weeks-and only if kidney function is normal.

Gabapentin and pregabalin? They’re often used for nerve pain, but studies show they only reduce pain by about 1 point on a 10-point scale. Meanwhile, they cause dizziness, confusion, and falls. The JAMA study found that after the 2016 CDC guidelines, many seniors were pushed onto these drugs instead of opioids-only to end up worse off.

Physical therapy, heat/cold therapy, acupuncture, and cognitive behavioral therapy for pain (CBT) are far safer and often more effective long-term. But they take time and commitment. That’s why opioids still have a place-for patients with cancer, severe arthritis, or post-surgical pain who need immediate relief.

Monitoring Is Not Optional

Starting an opioid is just the beginning. Monitoring is where safety happens.

The Medical Board of California requires clinicians to check in regularly: every 1-3 months at first. They look for:

- Is pain improving? Not just the number on a scale-but can the patient get out of bed? Walk to the bathroom? Sleep through the night?

- Are there signs of confusion, drowsiness, or slurred speech? These could mean opioid-induced delirium.

- Is constipation being managed? Laxatives should be prescribed from day one.

- Is the patient falling more? A simple balance test can catch rising fall risk.

- Are there signs of misuse? Urine drug screens help confirm the patient is taking what’s prescribed.

Also, never skip a treatment agreement if opioid therapy lasts longer than three months. It’s not about distrust-it’s about clarity. The patient should know the goals: "We’re aiming to help you walk to the kitchen without pain, not to eliminate every ache." That keeps expectations realistic.

What the Guidelines Got Wrong-and How They Fixed It

In 2016, the CDC released opioid guidelines meant to curb misuse. But they were applied too broadly. Doctors started refusing opioids to cancer patients, nursing home residents, and those with end-stage arthritis. The result? Untreated pain. More suffering. More emergency visits.

The 2022 CDC update corrected this. It explicitly said: "These guidelines do not apply to patients with cancer, palliative care, or end-of-life pain." It also said: "Don’t use rigid dose limits. Use clinical judgment."

That’s a game-changer. The American Geriatrics Society, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network all agree: opioids are the first-line treatment for moderate-to-severe cancer pain. About 75% of patients respond well. Pain drops by half on average.

But here’s the catch: if you start too high or move too fast, you can harm someone who could have been helped. That’s why individualization matters more than ever.

What’s Next for Senior Pain Care

The future is personal. Pharmacogenetic testing-where a simple cheek swab shows how a person metabolizes drugs-is becoming more accessible. Some seniors respond poorly to oxycodone but do great with hydromorphone. Testing can tell you that before you start.

Non-drug options are expanding too. Targeted nerve blocks, spinal cord stimulators, and wearable TENS units are now covered by Medicare in more cases. Physical therapy programs designed for older adults are proving just as effective as pills for back and knee pain.

But for now, opioids still have a role. And when used right-with low doses, slow titration, close monitoring, and constant communication-they can give seniors back their independence. Not just less pain. More life.

Are opioids ever safe for seniors with dementia?

Opioids can be used cautiously in seniors with mild to moderate dementia if pain is clearly documented-like a hip fracture or severe arthritis. But they require extra monitoring because confusion can mask both pain and side effects. Never start opioids in someone with advanced dementia unless pain is confirmed through behavior changes (grimacing, refusal to move, agitation) and other causes have been ruled out. Always involve family and caregivers in decision-making.

Can I use a fentanyl patch for an elderly person?

Fentanyl patches are not recommended for opioid-naïve seniors. They deliver a constant, high dose over 72 hours. If the person’s metabolism slows or they become dehydrated, the drug builds up dangerously. Fentanyl patches should only be used after the patient has already been stabilized on oral opioids for at least a week and has shown tolerance. Even then, start with the lowest available patch (12 mcg/hour) and monitor closely.

Why is constipation such a big deal with opioids in seniors?

Constipation affects nearly all seniors on opioids. But in older adults, it’s not just uncomfortable-it’s dangerous. Severe constipation can lead to bowel obstruction, urinary retention, and even delirium. It also causes falls if the person strains too hard. That’s why laxatives (like polyethylene glycol or senna) are prescribed from day one. Stool softeners alone aren’t enough. Regular bowel routines, hydration, and fiber are essential too.

Is tramadol really unsafe for seniors?

Tramadol isn’t banned, but it’s risky. It’s metabolized by the liver into a stronger opioid, and many seniors have reduced liver function. It also increases serotonin levels, which can cause dangerous interactions with antidepressants. Studies show it causes more dizziness and falls than other opioids in older adults. It’s also less effective for moderate-to-severe pain. Most experts now reserve tramadol for very mild pain and only if no other options exist.

How often should seniors on opioids have blood tests?

Routine blood tests aren’t required for most seniors on opioids. But kidney and liver function should be checked before starting and then every 3-6 months, especially if the patient is over 80 or has existing kidney disease. If the patient is on long-term therapy, annual liver panels and electrolyte checks help catch early signs of toxicity. Urine drug screens are more useful than blood tests-they confirm adherence and detect undisclosed medications.

11 Comments

Write a comment

More Articles

International Supply Chains and the Drug Shortage Crisis: Why Relying on Foreign Manufacturing Is Risky

International supply chains are critical to drug availability-but overreliance on foreign manufacturing has made the system fragile. When disruptions hit, patients pay the price. Here's how dependency on China and India leads to shortages-and what’s being done to fix it.

The Role of Azilsartan in Treating Hypertension in Pregnant Women

As a copywriter, I've recently come across the topic of Azilsartan and its role in treating hypertension in pregnant women. It's interesting to know that this medication can help manage high blood pressure during pregnancy, ensuring the well-being of both mother and baby. It's essential to maintain a healthy blood pressure, as uncontrolled hypertension could lead to complications such as preeclampsia. However, it's important to consult with a healthcare professional before taking Azilsartan, as they will be able to determine if it's the right treatment option. Overall, Azilsartan seems to be a promising solution for managing hypertension in pregnant women, contributing to healthier pregnancies.

Breakthrough Restless Legs Syndrome Treatments in 2025: Latest Hopes for Relief

2025 is showing real progress for people battling Restless Legs Syndrome. Cutting-edge drugs and exciting non-drug therapies are giving new hope. This article dives deep into the genuine breakthroughs—what's working, how UK patients are coping, and which emerging options you should know about. Find out about new medicines like amantadine and why lifestyle changes are getting attention from experts. Everything here is down-to-earth, practical, and aimed at helping real sufferers finally get some rest.

Patrick Jarillon

February 8, 2026 AT 02:12Let me guess - this whole thing was written by Big Pharma shills. Opioids? They’re not dangerous, they’re a government mind-control tool disguised as pain relief. Did you know the FDA approved morphine in 1903 to pacify rebellious farmers? Yeah, it’s all connected. I’ve got sources. I’ve got spreadsheets. I’ve got a cousin who works at a compounding pharmacy in Belfast. You think your 2.5 mg dose is safe? Try 0.7 mg. Or better yet - just drink turmeric tea and scream into a pillow. That’s real medicine.